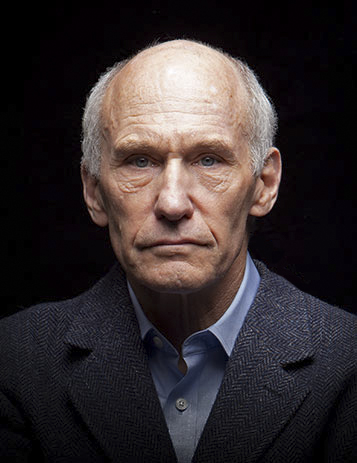

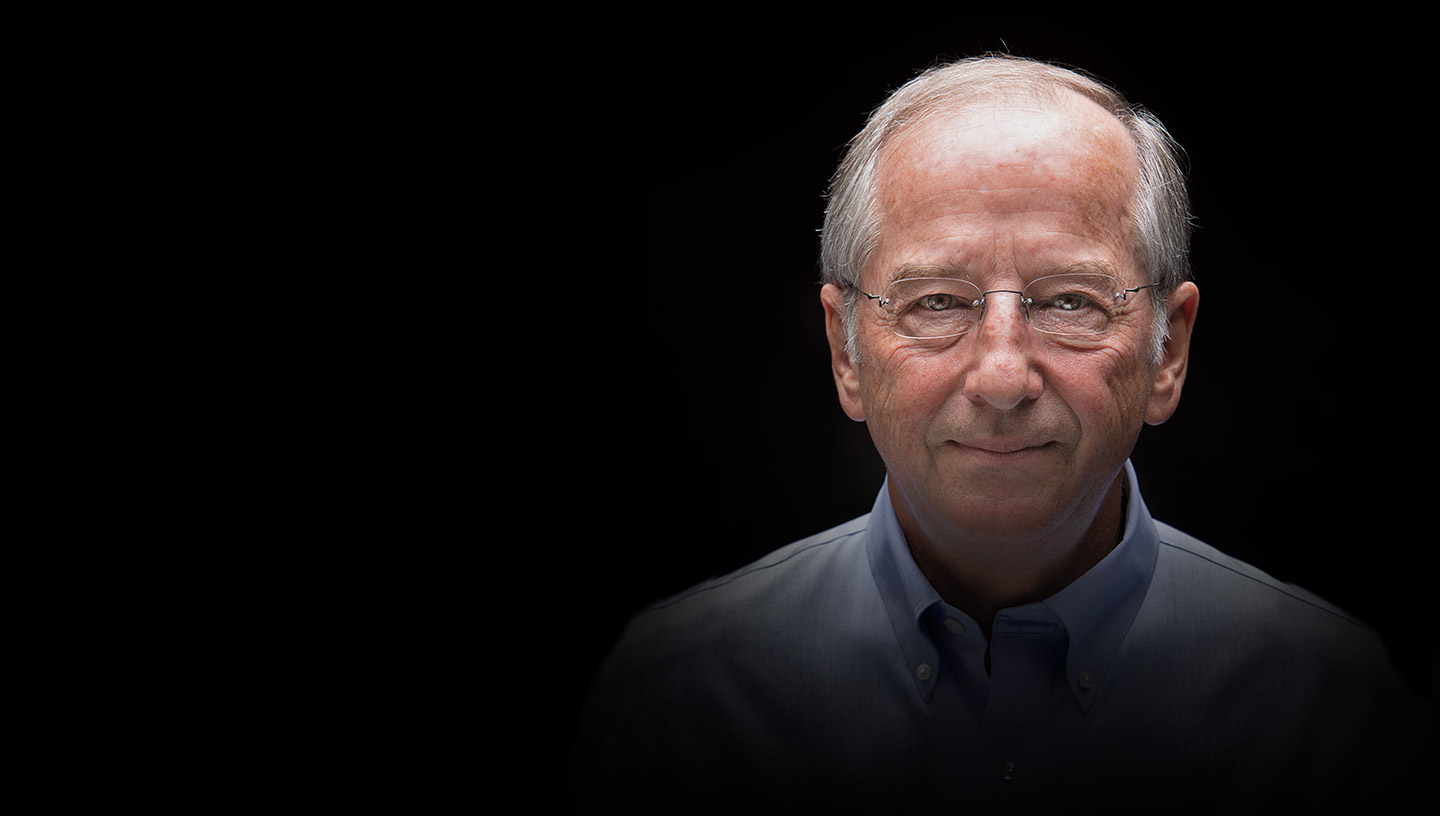

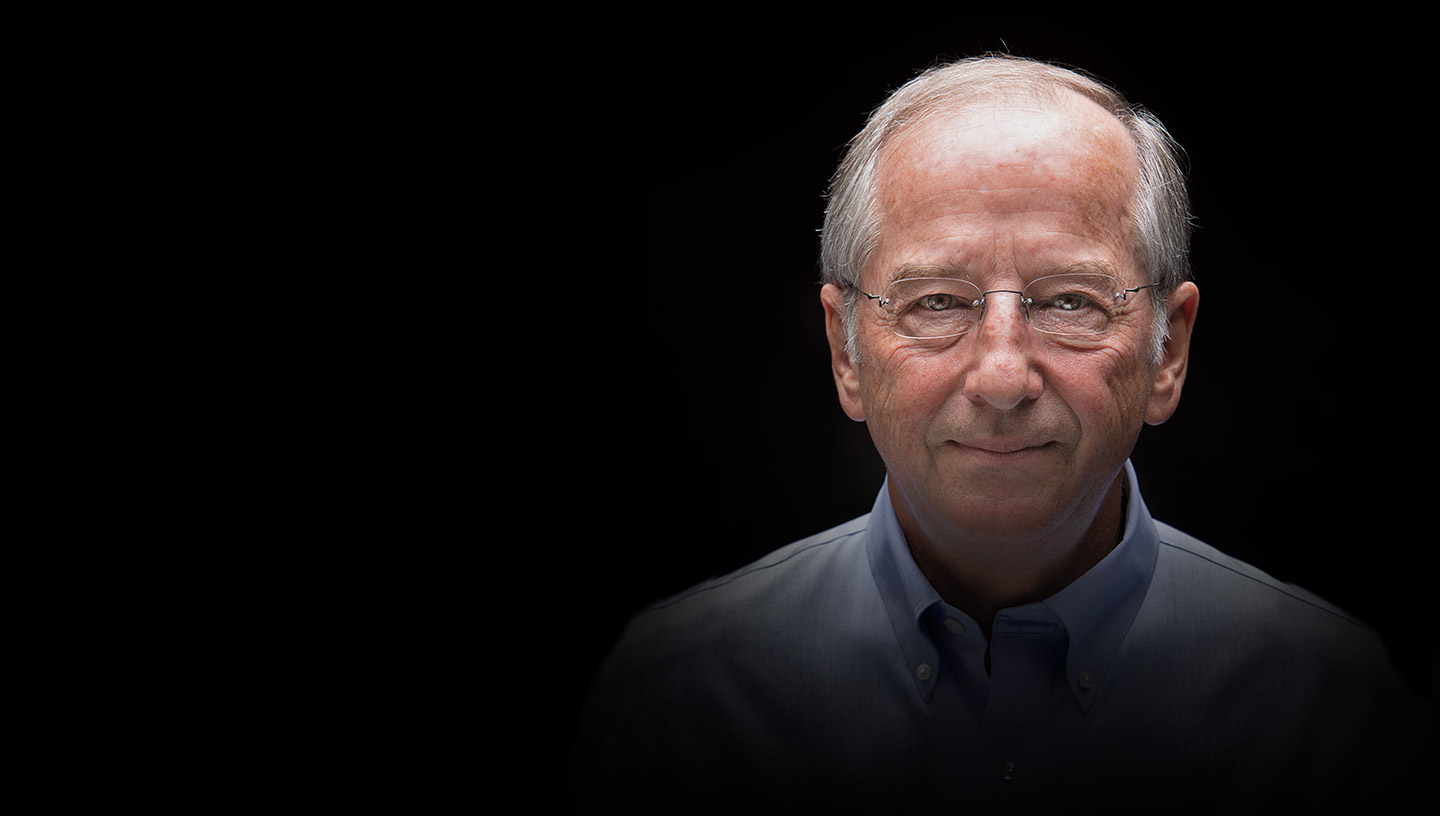

DR. MICHAEL

SAVING PATIENTS ON THEIR LAST BREATH

DR. MICHAEL WELSH BREATHED LIFE-SAVING DISCOVERIES INTO CYSTIC FIBROSIS CARE.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disease that affects 70,000 people worldwide. But for years, little was known about it. Dr. Michael Welsh pioneered the field of CF by identifying how it disrupts the lungs. He went on to study four kinds of genetic mutation that cause the disease and prove they can be treated, developing a roadmap that guided drug creation for life-saving therapies for 90% of patients. For his compassion and dedication to a cure, he’s nominated for the Sanford Lorraine Cross Award.

1981

PURSUING A PASSION

Dr. Welsh begins teaching at the University of Iowa as an assistant professor and pursues his passion for research.

1985

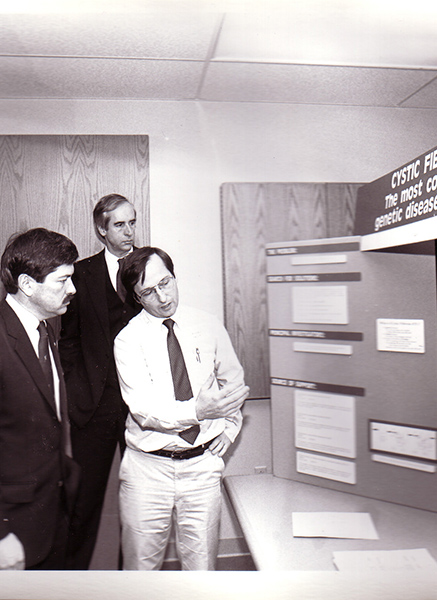

STARTING WITH WHY

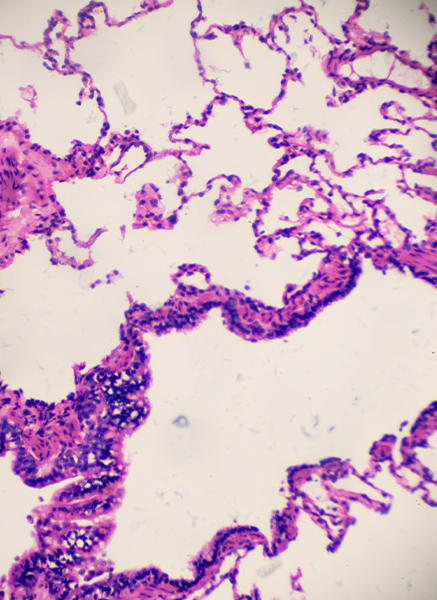

Dr. Welsh shows that CF patients’ lungs fail to transfer chloride back and forth through the epithelium. Without this ability, their lungs cannot clear out harmful bacteria.

1989

A DNA DISCOVERY

The defective gene in CF patients is pinpointed.

1990

THE BREAKTHROUGH

Dr. Welsh’s work uncovers that this gene makes the CFTR protein, which creates a pore that allows chloride transfer and confirms past findings.

1992

PROVING POSSIBILITIES

By conducting experiments with low incubation temperature, Dr. Welsh’s lab proves that it’s possible to treat this genetic defect.

1993

CREATING THE ROADMAP

Dr. Welsh and team classify four types of CFTR mutations, creating a roadmap for future cystic fibrosis treatments.

2008

NEW MODELS OF THINKING

Dr. Welsh develops a pig model to study CF and lung disease – a groundbreaking, more accurate way to study the disease versus typical mouse models.

2019

AN ANSWER FOR PATIENTS

Dr. Welsh’s roadmap leads to treatment breakthroughs as Trikafta is FDA approved for those with a CFTR mutation, helping 90% of CF patients.

“It ignited drug companies, it ignited academics, and it said, ‘It’s going to be possible.’ And that roadmap has guided the field ever since.”

DR. MICHAEL WELSH

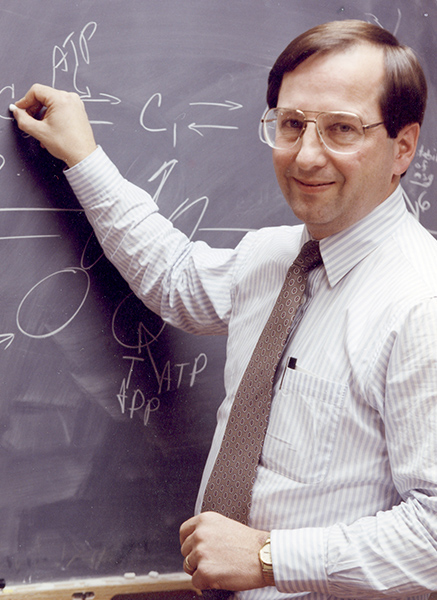

ASKING THE MOST IMPORTANT QUESTIONS

Dr. Michael Welsh was born and raised in Iowa. But his discoveries in cystic fibrosis have reached the farthest parts of the globe, impacting patients around the world.

“When I started, what we knew about cystic fibrosis was pretty limited,” says Dr. Welsh.

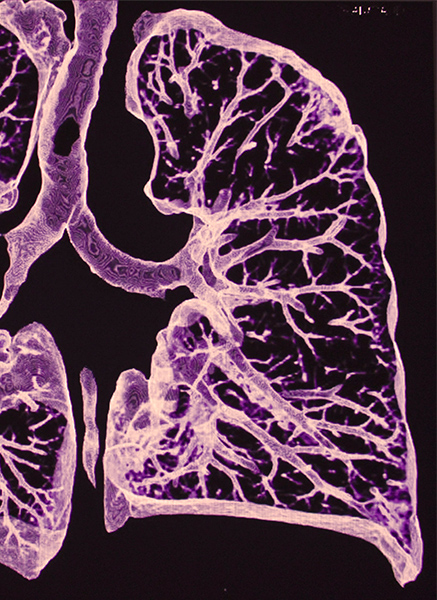

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disease that affects 70,000 people. Patients have chronic lung infections, and multiple organs like the pancreas are affected by the disease. Early on, the disease was a death sentence for children, who rarely lived to see adulthood.

In addition to lung problems, CF patients also share one other unique side effect.

“We knew they had salty sweat. I got interested in that because of the observation ab11out the sweat glands,” he says. Dr. Welsh had previously studied issues with the sweat glands and chloride transfer in the intestine during his postdoctoral work.

“It made me think, ‘I wonder if the same thing is going on in the lung?’ And then I began my studies focusing on cystic fibrosis.”

After studying the cells of the lung extensively, Dr. Welsh and his team found that the large sheet of cells that lines the lungs, called the epithelium, usually transfers salt (or chloride) back and forth from the body into the lung. This chloride helps the lung clear out bacteria to protect itself from infection. And in CF patients, there’s a problem with this transfer process.

Then, in 1989 the gene mutation for CF was uncovered. And it connected the dots from this initial discovery to one that opened new doors.

“That gene is a set of instructions to make the CFTR protein,” Dr Welsh says. “And we ultimately found that protein makes a little pore to let the chloride flow out. Now we had something that allows chloride to move through, and it suddenly tied together what we knew before the gene and after.”

Dr. Welsh now had a target to aim at for developing CF treatments and a potential cure.

THE ROADMAP TO TREAT 90% OF CF PATIENTS

Once this connection was made, Dr. Welsh and his team got to work studying genetic mutations in CF patients. They successfully classified four types of mutations. Moreover, they conducted experiments that showed how doing things like lowering the body temperature could remedy the mutation. Meaning treatment and a solution were possible.

Dr. Welsh’s findings were critical to developing a roadmap for new treatments – one that’s still the field’s guiding light today.

“It ignited drug companies, and it said, ‘Here’s the problem. Here’s what we need to target. Here’s how we can do it.’”

This roadmap has led to the development of modern CF drugs like Trikafta, which can treat 90% of patients. This has changed CF from a disease that kills children into one that patients can live with into adulthood.

“90% of the people with CF have a highly effective treatment. Their lives are changed,” says Dr. Welsh “But of course, that leaves 10% who don’t have a treatment. So that’s one of the main areas on which we’re focusing now.”

Dr. Welsh’s lab has since developed new methods for studying lung disease, including a more accurate pig model instead of traditional mouse models for animal studies. His lab is forging ahead on gene therapy research to help that last 10% of CF patients. And through his efforts in neuroscience, he’s working on Parkinson’s therapies as well.

“The thing that was always first was the patients. And that empathy is a central part of being a physician-scientist.”

DR. MICHAEL WELSH